At Shanghai Huaer Collegiate School Kunshan, Carol Santos draws on a depth of experience to instill equity and understanding in teachers and students alike.

Even as a little girl, Carol Santos, the founding head of Huaer Collegiate, gravitated towards education. “I was that kid who went to school and came home and played school,” she says. “Some kids play with dolls or video games. I literally played school.”

So when an opportunity to create a school entirely from scratch in China presented itself, she was thrilled and excited. Dipont Education, a pioneering company in Chinese international education, was launching the school in a bustling province just west of China’s biggest city, Shanghai. Santos would be tasked with developing the curriculum, hiring staff, and creating the school’s philosophy. It was both a daunting prospect and a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

With an established reputation in China, Dipont presented a perfect match for Santos, an experienced educator who also happened to have an appetite for challenge. Over the past 20 years, the company has set up almost 30 programs working with schools across China and has established four K-through 12 independent schools. It partners with leading British institutions like King’s College School in Wimbledon to offer a blended education to Chinese students planning to study overseas. Santos’ school, Huaer Collegiate in Kunshan, would be the first Dipont school to prepare students to follow a curriculum with distinctive American elements.

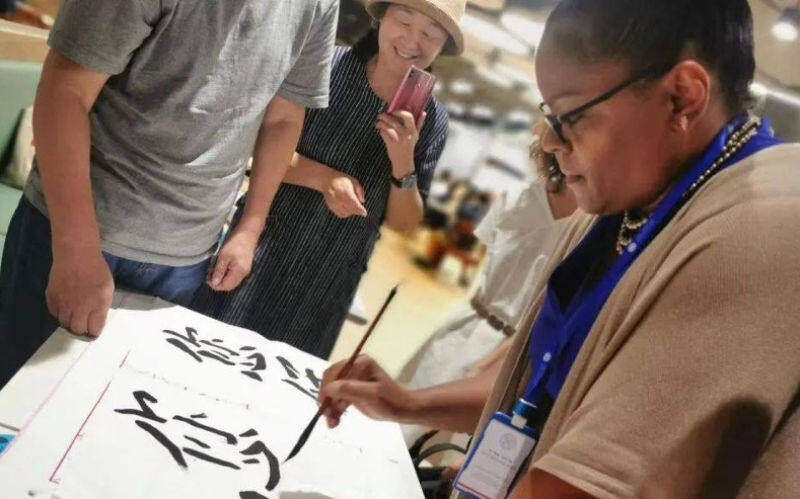

The company’s ethos chimed with Santos’ personal convictions, honed after decades in secondary education and leadership. For her, global education is the ideal education for any student. Dipont Education originated in China, and the company’s strong Chinese connections ground it in local culture while its vision for contemporary education aims to integrate the best of Chinese and Western practices. “It truly is two worlds coming together,” Santos says.

The Impact of Mentors

Santos has spent much of her career in teaching and leadership positions in top private US schools. Over the past 25 years, she taught at Westover, a private girls’ school in Middlebury, Connecticut, Groton School in Massachusetts, and at Miss Porter’s School, a renowned girls’ boarding school also in Connecticut. Most recently she was head of Centennial Academy, a public day school in Atlanta, Georgia, where she spearheaded efforts to improve the students’ academic performance and embrace a culture of excellence. Her dedication to young people is underpinned by her own early experiences. Although she was a good student, she says, “I didn’t always feel good about being a good student. And I didn’t always feel good about being a black girl. And that had to do with experiences in school and about school.”

Growing up in a working-class neighborhood in Connecticut that was socio-economically mixed, Santos was targeted by others because of her high grades. Later, she formed part of a generation of students involved in “busing”— a policy of bringing black and economically disadvantaged students to schools in white neighborhoods, to encourage integration. Santos ended up being the only African-American student in her class. “We were very much aware that the families who attended that school didn’t want us to be there. As young people we were like, ‘We’re going to stick together.’ But I ended up on my own and isolated.”

As she went through the system, though, individual teachers offered a helping hand at pivotal moments and helped to guide her path. When she moved to high school she initially decided to take less challenging classes so as not to attract unwanted attention and another socially disconnected existence in school. But one day, an English teacher overheard her in the corridor telling another student she would not study Shakespeare. The teacher was astonished that a talented student would make that choice and confronted her—ultimately calling her mom to voice her concerns. “The next thing you know my whole schedule was changed and I was in all these advanced college prep classes,” Santos says. She went on to study business, earning a degree in economics at the University of Pennsylvania and has a Master’s in Education from Columbia University. She is also undertaking a doctorate in educational leadership at UPenn. “That teacher really changed the trajectory of my life.”

Bridging Cultures

Speaking on screen from her office in Kunshan, Santos expresses herself thoughtfully, giving weight and meaning to every word. Leaving her home in Georgia was not a straightforward choice. She has two children who stayed in the US, a 23-year-old daughter and a 17-year-old son, but her son, in particular, urged her to seize the opportunity. She misses them a lot – and hopes it will be possible to return for her son’s graduation. “He may have an online graduation and if he has an online graduation at least I’ll feel as though I have the same experience as the other parents. I won’t feel so far away.”

In spring 2019 Santos traveled to China, meeting colleagues and beginning to assemble a team. It was a daunting task, which she likens to building a plane while also flying it. The process was facilitated by an excellent, smooth-running leadership team. “That was a blessing, that we could trust each other,” Santos recalls. “I think that probably is a key element.”

Moving to a new culture brings its benefits and drawbacks. Santos has acquired a love of Chinese cuisine – noodles, and stews in which meat falls off the bone. But if you ask what is lacking, the answer is simple. “I’m from New England, very close to New York, we’ve got good pizza where I’m from,” she says. “I have to tell you I’ve been missing pizza since I moved to Atlanta because their pizza is not as good as it is up north in the States. But their pizza is better than Chinese pizza.”

As an American woman heading an establishment in China, Santos has brought fresh ideas to overseas schooling. Typically, in private international schools, girls wear skirts or dresses as part of the uniform. But she pushed for the idea that girls could wear pants, sending photos of family friends to suppliers to convince them the right cut was possible. Despite its novelty, when winter fell, parents were clamoring. “I’ll tell you the parents and the girls are like, ‘It’s cold! Where are the pants? We want these pant options.’”

She finds her Chinese peers inordinately polite and respectful—sometimes excessively so. When colors for the school uniform were being discussed, Santos made her choice and presented it to the school’s leaders. She soon sensed that something was amiss. “They gave me a palette and I made a choice, ‘Okay, that one.’ I could have picked that one or another one within that shade or family. It really was not that big of a deal to me.”

She could tell they felt uncomfortable about openly disputing her choice. But they didn’t need to be. “All they had to say was, we like this shade better than that one because it looks better on Chinese skin. I could tell it was a heavy thing to them and I think more so because they were concerned about offending me.”

Please note that since January 2022, Shanghai Huaer Collegiate School Kunshan has been known as Dipont Huayao Collegiate School Kunshan.